Reading Between the Lines: State Department Cable Reveals Alarming New Visa Vetting Policy

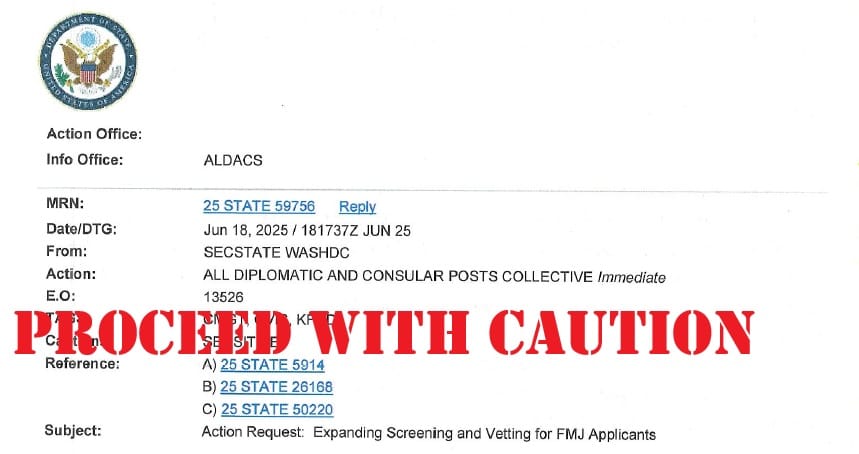

As a former Foreign Service Officer now practicing immigration law, I’ve stood on the other side of the plexiglass, adjudicating over 12,000 nonimmigrant visas and making split-second decisions that changed lives. So I’ve pounced on the Department of State (DOS) cable dated June 18, 2025. It outlines a new social media and online presence vetting procedure so burdensome and ill-conceived that it appears intentionally designed to bog down visa processing more than to effectively root out nefarious visa applicants.

For the hundreds of thousands of F-1 and M-1 international students and J-1 exchange visitors hoping to come to the U.S. (or come back after international travel), the State Department’s new policy presents a huge new hurdle. It mandates a significant new workload for consular officers without adding funding or staff, so visa processing will undoubtedly slow down.

The State Department uses cables to convey official information between U.S. Embassies and Consulates and Main State in Washington, D.C. The embassy serves as the official diplomatic mission of the United States in a host country and plays a crucial role in international relations. These cables are sent to and from embassies located in many different countries, reflecting the global scope of diplomatic communications. Cables often function as official reports prepared by embassy staff to inform the State Department of developments and events in their host countries. Cables can communicate new policies and procedural changes to consular officers, updating them on visa processing, security measures, or other consular operations. The idea is to get everybody on the same page and implement policy quickly and consistently across every different consular post.

The language of the June 18 cable “Action Request: Expanding Screening and Vetting for FMJ Applicants” really concerns me because it creates a minefield of subjective standards and procedural black holes. The State Department’s new policy is built on vague, subjective criteria that will encourage arbitrary decision-making, when consular officers already have extremely wide discretion to deny visas based on their gut feelings. I worry that this new policy could double the consular workload at some posts, creating significant delays for F, M, and J visas, and bogging down other visa categories as well.

The cable directs consular officers to “identify applicants who bear hostile attitudes toward our citizens, culture, government, institutions, or founding principles; who advocate for, aid, or support designated foreign terrorists and other threats to U.S. national security; or who perpetrate unlawful antisemitic harassment or violence” to further the mandate from Trump’s Executive Order “Protecting the United States from Foreign Terrorists and Other National Security and Public Safety Threats.”

A Look Inside the Mandate: Analyzing State Department Cables' Alarming Language

The directive moves far beyond previous guidance, establishing a new, sweeping, and highly subjective standard of review. In addition to being deeply problematic, the new policy is operationally unworkable at current staffing and funding levels.

The Danger of Vague and Subjective Criteria

The cable directs officers to conduct a "comprehensive and thorough vetting" to identify applicants who exhibit certain characteristics. But the definitions provided are incredibly broad and open to interpretation. Officers must screen for applicants who “bear hostile attitudes toward our citizens, culture, government, institutions, or founding principles.”

What constitutes a “hostile attitude?” Is it a meme mocking President Trump that you shared on social media hostile? What if you didn't post it, but you “liked” it? What about your scholarly critique of a U.S. government policy? A debate you participated in at a university forum?

The cable provides no objective definition, leaving it entirely to the discretion of the individual consular officer. This ambiguity is a recipe for inconsistent adjudications, where a visa applicant's fate will hinge on the consular officer's personal biases or their (mis)interpretation of cultural or linguistic nuance. The directive also targets those who “perpetrate unlawful antisemitic harassment or violence,” another term that requires careful, consistent application. I worry that it could easily be used to justify denial of anyone with pro-Gaza content in their social media.

If you have been following the stories of the Columbia grad student Mahmoud Khalil, Columbia PhD student Ranjani Srinivasan, or Tufts PhD student Rumeysa Ozturk, you know how ugly it can get for a foreign student when the government notices their political activism, even if they've never broken the law or hurt anyone.

Privacy is Now Potentially Evasive

The new policy’s stance on digital privacy is equal parts chilling and ridiculous. While e-mail is now a common form of official communication, diplomatic cables remain the formal and authoritative channel for conveying sensitive information. The June 18 cable instructs officers to review an applicant’s “entire online presence” using all available resources, including social media. To facilitate this, applicants are now supposed to set their social media accounts to “public.” What if you value your privacy?

A limited or private online presence can be viewed with suspicion. This directive effectively penalizes applicants for maintaining normal digital boundaries, forcing them to choose between surrendering their privacy or being flagged as uncooperative and suspicious.

“Comprehensive” and “Thorough” as a Mandate for Delay

The cable repeatedly uses phrases like “comprehensive and thorough vetting” and explicitly states there are “no production or processing quotas.” Now consider that consular operations are funded through visa application fees, but every single case subject to heightened scrutiny is going to take much longer than it would have without it.

As a former consular officer, I know the pressure to adjudicate cases efficiently. Mandating a "comprehensive" review for every single F, M, and J visa applicant is a fundamental operational shift that guarantees a massive bottleneck. It is not possible to slam through 100+ visa applications a day if you need to stop and peruse every F-1 student's Instagram account (as well as their Google Scholar page, and LinkedIn profile, and Facebook activity, and YouTube comments, and hot takes on Reddit…). As those of us who have engaged in Internet stalking well know, there is a lot to dig through as you search someone's digital footprint.

Would you dress and behave the same at a dance club as in your visa interview? Beware, the cable warns consular officers that any inconsistency is suspicious: “be alert to any inconsistencies between what you discover during vetting and how the applicant presented himself in his application, in his supporting evidence, or during the interview. You must explore all such inconsistencies to ensure they do not indicate visa ineligibilities. Even when such inconsistencies do not point to an INA 212(a) ineligibility, they can call into question the applicant's credibility.” I've got to admit, it creeps me out to think of all these poor consular officers trolling through teenagers' party pics looking for any sign of scandal.

For the record, the DS-160 form asks for social media identifiers or handles used by the visa applicant on the following platforms within the last five years:

Douban

Twoo

Qzone (QQ)

Vine

Flickr

VKontakte (VK)

Google+

Sina Weibo

Youku

Tencent Weibo

YouTube

Tumblr

MySpace

Twitter aka X

Leave your First Amendment Rights at the Door

In addition to calling out the risk of terrorism, the cable points out that lots of international students wrongly aspire to remain in the U.S. after their course of study, or they may work illegally on the side. And worst of all, they may disturb us with their pesky political opinions: “for applicants who demonstrate a history of political activism… you must consider the likelihood they would continue such activity in the United States and, if so, whether such activity is consistent with the nonimmigrant visa classification they seek. As Secretary Rubio has said, we do not seek to import activists who will disrupt and undermine scholarly activity at U.S. universities.”

The 221(g) Refusal as a Procedural Black Hole

The new policy requires that all visa applicants who pass their initial interview be formally refused under Immigration and Nationality Act Section 221(g) to allow for this new vetting after their visa interview. Although 221(g) reversible denials have long existed for sparing use on those handful of cases where the consular officer isn't able to approve or deny the visa on the spot, shunting a huge volume of cases into Administrative Processing is a radical departure from standard practice. A 221(g) refusal puts the visa applicant into an open-ended state of limbo with no clear timeline for resolution. Under this new policy, 221(g) becomes the default for every student and exchange visitor visa applicant, creating a systemic, indefinite delay that is going to compound and worsen every day as the consular officers fall deeper and deeper into a hole.

When I was a consular officer working on the visa line, we each spent the vast majority of our working day actually in the visa window conducting the interviews. After getting through all the interviews scheduled for the day, we went to our desks to handle other work, including checking up on our cases where we had hit pause with a 221(g). When those cases were resolved to our satisfaction, we reopened and approved or denied them. It's not a fast or automated process. And in the majority of cases with a 221(g), we had not hung onto the applicant's passport and so still had to coordinate for them to give it to us to get the visa stamped.

Double Workload, Information Overload, Same Workforce

If you thought that the consulates could avail themselves of AI or the more numerous, lower-paid, and more culturally knowledgeable Locally Employed Staff to get through the monumental tasks dumped on them in this cable, think again. The cable lays out an onerous process that is supposed to be completed in each instance by the same consular officer who did the visa interview. It entails “a review of the applicant's entire online presence -- not just social media activity -- using any appropriate search engines or other online resources. It also should include a check of any databases to which the consular section has access (e.g., LexisNexis or local equivalents).” Don't worry, the cable insists repeatedly that everyone should just “take the time necessary to satisfy themselves,” worsening backlog be damned.

This isn't just a minor administrative tweak; it's a fundamental change to the process that is mathematically unsustainable. In Fiscal Year 2024, the U.S. issued over 400,000 F-1 visas and over 300,000 J-1 visas. That's over 700,000 visa applicants who would now be subject to a post-interview intensive manual review, not just for their first visa, but every single time they need to renew it.

A typical F-1 or J-1 visa interview lasts about two to five minutes. A conservative estimate for a meaningful “online presence” review is at least ten additional minutes (right?). Honestly, only 10 minutes seems inadequate, considering the new tasks: “You must document the results of your vetting in detailed case notes, including all potentially derogatory information and inconsistencies. If you find any relevant information online, take screenshots to preserve the record against possible later alteration or loss of the information and upload those screenshots to the applicant's case record in the CCD.” In comparison, the normal visa interview notes recorded by the consular officer during an interview very rarely exceed 50 words.

This new workload can't be met by simply hiring more officers, especially not on the absurd five-day implementation timeline. Consular officers don't grow on trees, and they can't live in trees either. It's a big lift to increase staffing at a consular post, requiring very long lead times (especially when the post requires foreign language proficiency, as most do). Then each new consular officer needs housing at post. Where does the money come from to pay for all this? Ultimately it comes from the visa application fees, which are per applicant, regardless of how long or short the process takes.

The Practical Challenges

The State Department's new policy is fraught with practical and logistical problems that will compound the delays.

The Language Barrier

The policy assumes consular officers can effectively vet someone's online presence in any language. As someone professionally fluent in Spanish and French, I can tell you that understanding cultural context, slang, and nuance is critical, and completely unrealistic even for consular officers who have received extensive and high-quality language training. Expecting a 30-year-old American consular officer who doesn't speak a language natively to accurately interpret social media posts by foreign 18-year-olds is a recipe for misinterpretation and unfair denials. Or as my tween would say, “that's suss.”

The Inevitable Impact on Wait Times

With a fixed number of officers and a massive increase in workload per F, M, and J visa applicant, the only rational outcome is a dramatic increase in visa processing times. It will become harder to get a visa interview, and then the time from the interview date to visa issuance will be much longer, and get worse over time. This is particularly problematic for students who, of course, have rigid academic calendars. If you don't get your visa in time for the beginning of the semester, how many days of class can you miss before you can't come at all?

The effect of these delays will not be limited to F-1 and M-1 students and J-1 exchange visitors. I anticipate a cascading effect, with slower processing for all other nonimmigrant visa categories as consular resources are stretched to their breaking point. And if nonimmigrant visa operations borrow manpower from immigrant visa operations, you can expect overseas green card processing to slow down as well.

Who is Impacted?

This cable applies to all F-1, F-2, J-1, J-2, M-1, and M-3 visa applicants. J-1 physicians and F-1 students who attend schools with no more than 15% international students are supposed to be prioritized, but are not exempt.

Among those affected by the State Department's June 18, 2025 cable will be the following visa categories:

J-1 Professors and Research Scholars: For individuals participating in research or teaching at U.S. institutions.

J-1 Short-term Scholars: For individuals coming to the U.S. for short-term academic activities.

J-1 Trainees and Interns: For individuals seeking training in U.S. businesses or institutions. For those interested in employment opportunities in the U.S., see the TN Visa Career Categories and Jobs List.

J-1 College and University Students: For students pursuing a full course of study at U.S. degree-granting institutions.

J-1 Teachers: For individuals teaching in primary and secondary schools.

J-1 Secondary School Students: For high school students participating in exchange programs.

J-1 Specialists: For experts in a field of specialized knowledge.

J-1 Physicians: For medical graduates participating in U.S. medical training programs.

J-1 Camp Counselors: For individuals working as counselors in U.S. summer camps.

J-1 Au Pairs: For young adults providing child care services while living with a host family.

J-1 Summer Work Travel: For students working and traveling in the U.S. during their summer vacation. For those curious about employment-based visa options, see this guide on L1 vs H1: Understanding the Differences.

J-1 Government Visitors: For individuals invited by U.S. government agencies to participate in exchange programs.

J-1 International Visitors: For individuals invited to the U.S. by the Department of State for observation tours, discussions, and consultations.

J-2 Dependents: the spouse or child of an J-1 exchange visitors (only some types of J-1 visas allow accompanying family).

F-1 Academic Students: students pursuing academic studies or language training programs at U.S. institutions such as colleges, universities, seminaries, conservatories, academic high schools, elementary schools, or language training programs.

F-1 Graduates with OPT or STEM OPT: a graduate of a U.S. institution who has been given authorization by their institution and USCIS to work in the U.S. for up to three years after graduation, while remaining in F-1 student status.

F-2 Dependents: the spouse or child of an F-1 student.

M-1 Vocational Students: students enrolled in vocational or other recognized nonacademic programs, excluding language training programs, at institutions approved by the Department of Homeland Security.

M-2 Dependents: the spouse or child of an M-1 student.

Foreign Policy Ripple Effects

The June 18 State Department cable is just the latest chapter in a long and storied tradition of diplomatic cables shaping the course of international relations. For centuries, governments have relied on confidential diplomatic cables to communicate sensitive information, coordinate foreign policy, and respond to world events. The term “cable” itself harks back to the 19th century, when telegraph cables—costly and cutting-edge at the time—first connected embassies and foreign ministries across continents. The high cost of sending diplomatic messages via telegraph cables led to a famously terse, almost Twitter-like style, where every word counted and secrecy was paramount.

While the technology has evolved—from telegraph cables and diplomatic pouches to encrypted email and secure digital networks—the core principles of diplomatic communication remain unchanged: confidentiality, clarity, and the ability to shape events from behind the scenes. Diplomatic cables have played pivotal roles in world history, from the infamous Zimmerman Telegram that helped draw the United States into the First World War, to the tense exchanges during the Cuban Missile Crisis that brought the world to the brink of nuclear war. These cables, whether sent by a German ambassador or a deputy assistant secretary, have often been the invisible threads pulling at the fabric of global events.

But the digital age has brought new challenges. The release of confidential diplomatic cables by WikiLeaks sent shockwaves through the world of diplomacy, exposing the inner workings of the State Department, foreign governments, and embassies. Suddenly, the secrecy that had long protected diplomatic messages was under siege, and the consequences rippled across international relations. Leaked documents revealed not just the content of top secret communications, but also the candid assessments, private doubts, and sometimes unvarnished opinions of diplomats and officials. The fallout was immediate: trust between nations was shaken, foreign ministries scrambled to reassure partners, and the media pounced on every revelation.

These events underscored the high stakes of diplomatic communication. In an era where information overload and instant news can amplify every word, the need for secure, confidential channels is more critical than ever. The United Nations and other international organizations continue to rely on diplomatic cables to coordinate responses to crises, negotiate peace, and maintain the delicate balance of power among nations. Yet, as technology advances, so do the risks—whether from hackers, whistleblowers, or the sheer volume of data moving through global networks.

The story of diplomatic cables is, at its heart, the story of diplomacy itself: a constant balancing act between openness and secrecy, between the need to inform and the need to protect. As the world becomes more interconnected, the importance of maintaining secure, confidential diplomatic communications only grows. Whether it’s a cable shaping visa policy or a diplomatic telegram averting war, these messages remain the lifeblood of international relations—reminding us that, in diplomacy, what’s said between the lines can change the course of history.

What This Means for You

If you are an F-1 or M-1 student, J-1 exchange visitor, or an institution sponsoring these individuals, you need to prepare for a much slower and more uncertain visa process.

- Apply for your Visa as Early as Possible: Standard processing times of a week or two are a thing of the past. You should now anticipate a process that could take many months.

- Prepare for Social Media Scrutiny: Be mindful of your online presence. And if you just delete everything and shut down your accounts, that could be held against you as well.

- Expect Delays and Plan Accordingly: This policy could impact your availability to get to the U.S. in time to start your academic program or exchange. Communicate with your sponsoring institution about potential delays and have contingency plans in place.

While the stated goal of the State Department's new vetting policy is to enhance security, its practical effect will be to create a bureaucratic nightmare that penalizes legitimate students, exchange visitors, and institutions. It damages the reputation of the United States as a welcoming destination for the world's best and brightest.

At Locke Immigration Law, we are dedicated to helping our clients navigate these complex and often frustrating challenges. We will be monitoring the implementation of this policy closely and are here to provide creative solutions and expert guidance. If you have concerns about how this new policy will impact you or your organization, please don't hesitate to reach out.

About the Author

Loren Locke is the Managing Attorney of Locke Immigration Law and a former U.S. Foreign Service Officer who adjudicated approximately 12,000 visa applications at the U.S. Consulate in Mexico. She holds a J.D. from William & Mary Law School and a B.A. summa cum laude from the University of Richmond. Loren is regularly quoted on immigration policy by major publications including Newsweek, Condé Nast Traveler, and The Daily Mail, and specializes in EB-1A extraordinary ability petitions, O-1 visas, and National Interest Waivers.

Follow Loren on LinkedIn | Watch on YouTube | Book a consultation | hello@lockeimmigration.com

Want to learn how to strategically frame your achievements for the EB1A "Extraordinary Ability" visa? My free 5-day email course, "5 Days to Your Compelling EB1A Story," provides the 'EB1A Storytelling Toolkit' to help you build a powerful case. Sign up here.